We hear a lot about multinational merger-and-acquisition forays into the craft beer industry. We hear much less about horizontal mergers between craft breweries.

It is notable that, whereas previous waves of transactional activity in the UK brewing industry have been characterised by consolidation, the wave of the past decade has been characterised by proliferation.

As breweries struggle to grow their businesses in a shrinking and competitive market, the main challenges are the same as they ever were: How do we make sure the consumer knows about us and our beer? And how do we get our beer to them?

Why, then, have these same challenges not led to the same industry dynamics?

I suspect the answer lies in another signature industry development of the current cycle: the collaboration beer. In concert with changes in the way beer is retailed, the “collab” arguably addresses those two age-old challenges of marketing and of distribution without the need for ruthless consolidation that characterised earlier cycles of industry reorganisation.

The two biggest cycles of UK brewing industry reorganisation occurred during the last two decades of the 19th century and the middle two decades of the 20th century. Both were periods of brutal consolidation. The first was driven by a scramble for distribution networks, and the second was driven by a combination of new dispensing technology and the development of nationwide brand marketing.

During the 1890s, the number of breweries in the UK pretty much halved. A revolution in quality control that followed a series of scandals involving arsenic in brewing sugar knocked out many of the very smallest concerns. At the same time, larger, industrial brewers faced a shrinking market as temperance movements went mainstream, and shrinking margins and cash flows as the Budget measures of 1880 took effect. The resulting scramble for growth saw brewers race to expand their estates of public houses in order to broaden their distribution networks. By 1900, 90% of the pubs in England and Wales were owned by breweries.

Buying all of that real estate was an expensive business. As brewing became ever more capital-intensive, it embraced the signal innovation of industrial capitalism: the joint stock company. Led by Arthur Guinness and Ind Coope, and then the Burton- and London-based breweries, more and more big brewers offered debentures or common stock to raise the funds necessary to buy pubs. That, in turn, led to a wave of consolidation among the mid-tier of breweries, as they clubbed together to form “united brewery companies” big enough to go on to public flotation.

If late-19th century consolidation was about the scramble for a real estate distribution network, mid-20th century consolidation was more straightforwardly about economies of scale―but it was also, as a consequence, about the emergence of genuinely nationwide beer marketing.

In some ways, the 1950s and 1960s, which saw the formation of the “Big Six” UK brewers—Allied, Bass Charrington, Courage, Scottish and Newcastle, Watney Mann and Whitbread—both completed the consolidation that began around the turn of the century but also started to undo its network of brewing real estate.

As the baby boom fed a growing demand for residential property, successive governments loosened building restrictions, ushering in a golden age for real estate developers. Many breweries owned extensive real estate portfolios in desirable suburban locations—both tied pubs and brewing facilities themselves―and as a result they became prime targets for the developers, who would buy the business, close the brewing operations and build homes on the land. Moreover, as the “Big Six” grew their market share, they too got involved in this lucrative property development business, adding further momentum to these pub and brewery closures. From the patchwork of regional tied-pub networks that characterised the first half of the 20th century, itself the result of a consolidation of the hyper-local brewing-and-distribution model of the mid-19th century, we moved to an ever-shrinking, but increasingly national distribution network of pubs tied to the Big Six.

That nationwide distribution was facilitated by the longer shelf life of pasteurised, “brewery-conditioned” beers destined for modern kegs. The ability to distribute those consistent, centrally-produced beers across the country created brands that could be grown still further, albeit at considerable cost, with the first genuinely national television, radio and press advertising campaigns.

The Campaign for Real Ale (CAMRA) and the embrace of the US-inspired craft-beer movement put all that behind us. But when the next industry reorganisation occurs, will the current proliferation of breweries yield to another wave of consolidation, pushed by the same forces that prevailed in the 1890s and the 1960s—the need for nationwide (and increasingly international) distribution and brand recognition?

This is where collaboration beers have an underappreciated importance. The “collab”, when executed well, helps to meet those two needs in a way that resists rather than requires consolidation. That may be why it has become such a staple ingredient in craft beer over the past 10 years.

When brewers talk about collaborations, they like to characterise them as a meeting of minds, old industry friends catching up for a burst of creativity, an opportunity to share knowledge, to clash beer styles together—in short, to experience the multiplicative effect of two groups of brewing geniuses being let loose on the same set of equipment at the same time.

In their more reflective moments, however, they will also concede that collaborations are at least as much about getting their brands into their collaborator’s distribution networks and in front of their consumers.

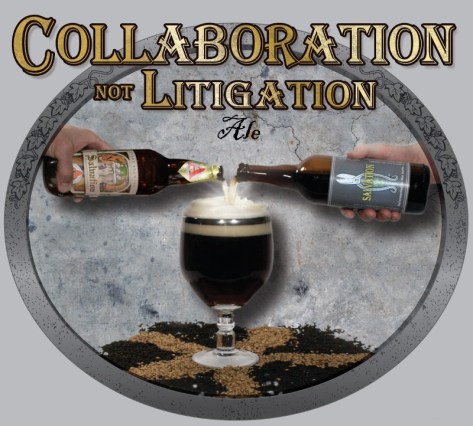

There are many candidates for the title of first ever collaboration beer, but perhaps the most pleasing origin myth is the one that stakes the claim for Collaboration Not Litigation Ale, first released in 2006 by Russian River Brewing of California and Avery Brewing of Colorado. It is pleasing because, like all the best origin myths, it embodies the tensions inherent in the idea it explains.

Both breweries make a Belgian-style ale called Salvation, and the story has it that these friendly rivals, rather than fighting over the brand name, decided instead produce a limited-edition product by blending the two beers.

In brewing terms, the process was arbitrary and of questionable value. Russian River’s Salvation is a Strong Dark Abbey Ale and Avery’s is a Golden Ale—the sole reason for blending them was the name. And while Collaboration Not Litigation Ale is presented as an emblem of the craft-beer ethic that elevates amicability above the big-business obsession with market share at all costs, that should not obscure the fact that the Salvation name became an issue only once these two breweries began to go national with their marketing and distribution. They were about to become competitors, but instead, Collaboration Not Litigation Ale turned a potential problem into a way to leverage one another’s profile in their respective markets.

Origin myth

The template for future “collabs” was set.

Many beer drinkers would agree that very few of the collaboration beers brewed since then would stand up as classics, even when the collaborators were drawn from the top rank. That shouldn’t surprise us. In most “collabs”, as with the supposed original, the beer is less important than the collaborators themselves. Are they in different countries, or different regions of the same country? Do they sit in different beer cultures or demographics (traditional cask versus modern craft, farmhouse versus urban)? Do they have overlapping distribution networks? Do their brands complement rather than challenge one another―are they close enough to resonate with the other’s consumers without threatening to usurp their loyalty?

This is why more and more collaborators are not other breweries at all, but musicians, bottle shops, bars, restaurants, fashion brands, sports stars and television shows.

Paradoxically, collaboration brewing works so well because today’s craft-beer industry is both unprecedentedly global, and yet arguably as local as it has been since the mid-19th century.

Craft beer distribution today has little to do with tied public houses, or even national bar chains. The off-licence trade revolves around independent bottle shops that stock mainly local products, and the global mail order services facilitated by the internet and advances in canning and logistics technologies. The on-licence trade consists of specialist craft-beer bars and brewery tap rooms which, like the bottle shops that are sometimes also on-licence tap rooms, have a distinctly local bias.

Marketing, of course, has moved off of national television and press to become, through social media, both truly and instantly global and minutely focused on the individual consumer, whose minimal brand loyalty must be continually excited. As a result, that marketing has moved away from building brand-consistency for individual beers, and towards a model of continual novelty and variety, underpinned by brand-consistency for individual brewing companies.

Collaborations enable brewers to expose their brands through those fragmented modern distribution networks, and an Instagram story of a collaborative brew day instantly reaches the followers of each collaborators’ brands, wherever they are around the world. Furthermore, the novelty of the collaboration beer fits snugly with the novelty and variety of the modern craft brewer’s product range.

Compared with the hugely expensive nationwide marketing and distribution efforts required 60 years ago, “collabs” are therefore remarkably low-risk for both parties. The best result for your competitor-collaborator will be to make a small inroad into what is still a very localised market for your product―a bit of shelf space at your local bottle shop for its flagship beer, a guest tap at your city’s bars every now and again. The worst result for you is that you fail a test in an entirely new market at the cost of clearing a few days on your brewing schedule and designing some funky one-off can art.

In that respect, for all their evident commercial hard-headedness, collaborations really are about spreading the word and sharing the love. In the past, achieving the nationwide marketing and distribution required to support growth meant a huge outlay of capital and advertising spend—and that demanded total and ruthless commitment to wiping out or absorbing the competition. Today, it’s all about taking mutual small bites out of the local market shares of a number of competitor-collaborators which, added together, amount to considerable growth for a small or medium-sized business, with nationwide or even international reach, but minimal risk.

This may well be a practice, and a commercial dynamic, that is unique to the craft-beer industry. And while it may not save all craft brewers from the industry’s next reorganisation, or even soften the blow of that reorganisation, the spirit of collaboration will prevent a repeat of the cannibalistic consolidations of the past.

Pingback: The Wages of Sin | Pursuit of Abbeyness