The two most significant trends in high-quality beer production over the past 40 years have arguably been the revival of real ale in the UK and the craft-beer movement in the US. Both trends laid an emphasis on freshness, for different reasons.

Real ale is a live product, undergoing secondary fermentation in its cask; and as the beer is dispensed it comes into contact with oxygen within the cask. While some time is therefore required for fermentation between filling the cask and serving the beer, thereafter, every passing hour is an hour closer to the beer being spoiled. A skilled cellarman might squeeze a week’s life out of a traditional British cask ale.

The popularity of US craft beer owes much to the extraordinary intensity and variety of citrus, pine and resin aromas imparted by American hops. Ironically, while the alpha and beta acids extracted from hops when they are boiled act as preservatives for the first few weeks of a beer’s life – which is why they were useful in the India Pale Ales of the 19th Century – the oxidation of those acids quickly causes their bittering and aromatic qualities to fade, and take on unpleasant “wet cardboard” flavours over time. The fresher a classic American IPA is, the better it will be.

And yet, in the background, traditions of cellaring and ageing beer have survived.

In the UK, some brewers have kept up the practice of creating bottled Old Ales or Barley Wines – the latter, especially, brewed to achieve such high levels of phenols and fusel alcohols that they are unpleasantly “hot” or spicy when young and only attain their true character after many years in storage. The tradition is arguably even stronger in Belgium, with its bottled- rather than cask-beer culture, its modestly-hopped, higher-ABV styles, and its important strand of mixed-fermentation, barrel-aged beers, such as Lambics, Gueuzes and Flemish Red and Brown ales.

Beers maturing in my cellar

Homebrewing makes one consider the practicalities of cellaring and ageing, too. After giving some of the 20-30 litres brewed to family and friends, you still like to keep a decent amount of your hard work to enjoy yourself. If you do not want to live on a daily diet of the beer you just happened to have made last week, that means favouring styles that can survive or thrive on a few months in a cool cupboard, a wine chiller, or a cellar. Make a hoppy beer, and, by contrast, you reconcile yourself to a big give away.

The oldest homebrew in my cellar was made almost two-and-a-half years ago. I have several large bottles of one style that was brewed specifically to age for at least 12 months. One beer that I made with a Saison-Brettanomyces yeast blend had an awkward clash of residual sweetness, cardamom spice and phenolic “funkiness” in its youth, but has matured into respectable adulthood after a year, as the Brettanomyces yeast has gradually increased its dryness and the spices have eased into the background.

A complete and delicious transformation

Looking beyond homebrew, over the past three years I have begun to collect Lambics, Gueuzes and Oude Krieks with a view to cellaring them for five years or more. Back in April, to celebrate my father’s 70th birthday, we drank a Fuller’s Vintage Ale that went into my cellar a decade ago, and marvelled at its heady mix of sherry, whisky, burnt orange, red cherries and leather – not to mention its 40% annualised (yes, annualised) rate of retail-price appreciation.

Last weekend I shared a Schneider Aventinus with my brother that was brewed in 2012 and spent three years in the brewery’s ice cellar and then two years in mine: it was truly astonishing how completely and deliciously this already-classic beer had changed, deepening many shades in colour to a burnished red-brown, losing its characteristic bubblegum flavour but compensating with an indulgent mix of over-ripe banana, vanilla, chocolate, toffee, raisin, dark rum and sherry.

An excellent introduction

And a couple of years ago we blind-tasted a six month-old Orval next to a five year-old bottle: there was no need for the blind element, however – the aged beer was unpleasantly thin and astringent, albeit with an intriguing, petroleum-like, noble-rot character in its aroma as it warmed in the glass.

Many different beers, many different cellaring periods, many and varying results.

It was with this experience behind me that I turned to a book by Patrick Dawson, Vintage Beer: A Taster’s Guide to Brews That Improve over Time (Storey Publishing, 2014), hoping for some explanation, insight and guidance. Did I find it? Certainly. The book is an excellent introduction to the concept of ageing beer. Nonetheless, a lack of detail and a sometimes-strange choice of emphasis left many questions unanswered.

The book is organised in six chapters, together with an introduction on the concept of beer ageing and an appendix on vintage-beer bars around the world. The first chapter covers the basics of what happens when a beer ages and establishes some handy essential “rules” to remember. The second chapter considers the chemical properties of beer’s many ingredients in order to determine which ingredients hold the best promise for ageing, and what happens when they are kept in the cellar. Chapter three extends these findings into a consideration of the six beer styles that Dawson considers best-suited for ageing. The fourth chapter narrows things down further, presenting detailed vertical tastings of eight specific beers. Chapters five and six cover the questions of optimal storage conditions and cellar management.

Patrick Dawson’s “Vintage Beer Rules”

1. Unless the beer is smoked or sour, the alcohol content should be at least 8% ABV.

2. A beer’s booziness eventually mellows and creates new, ageing-derived flavours.

3. Darker malts create sherry and port flavours with age.

4. Malt proteins drop out, causing a beer’s body to slowly thin.

5. Cloudy wheat proteins fall out quickly (after six months or so), leaving a clear, thinner beer.

6. Hoppiness fades over time and leaves behind either good or bad flavours, depending on the type of hops used.

7. Fruity yeast esters are volatile and change over time.

8. Spicy yeast phenols (pepper, clove, and smoke) develop into vanilla, leather and tobacco flavours when aged.

9. Oak-derived flavours from wood or barrel aging stay fairly constant over time.

10. Sour beers (Lambics, Gueuzes, Flanders Red Ale) soften over time.

11. Brettanomyces yeasts continue to ferment in the bottle, creating more phenols over time and a drier beer.

12. Unpasteurised beers are preferred because the yeast in the bottle helps them develop and integrate better over time.

13. Beers should be cellared below their fermentation temperatures (18°C for ales, 10°C for lagers).

14. A bottle’s size and closure type affect the rate at which it ages.

One very welcome aspect of the book is its lack of vintage-beer snobbery or didacticism. While Dawson concedes that, even among “craft beers”, less than 5% of everything produced is appropriate for aging, he does not equate freshness with a lack of sophistication or complexity. “Most will find that a two-week-old Bell’s Horsham Double IPA is on a par with a 20-year-old vintage Thomas Hardy’s Ale in the sense that they’re both world-class brews being consumed at their peak ages,” as he puts it. Even the six styles picked out for ageing (English Barley Wines and Old Ales, American Barley Wines, Imperial Stouts, Belgian “Quads”, Flanders Red and Brown Ales, and Gueuzes) are presented as a “safe-bet” list, rather than something exclusive or definitive.

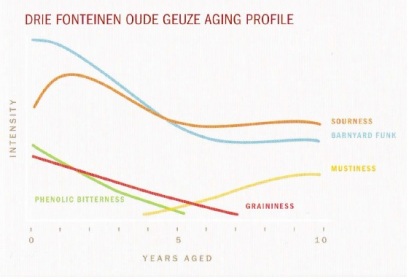

Similarly, while “each beer has a ‘window’ in which it can really shine”, the author acknowledges that “everyone’s optimal window is different, and it requires knowing what you are looking for in a beer”. A beer that ages well tastes different at years two and year five, not necessarily better, and this book, particularly chapter four with its “ageing profile charts” of beers’ flavour structures through time, is dedicated to helping us understand the ageing process so that we can make informed decisions based on our own tastes and preferences. A fine Gueuze does not have to languish for 20 years to be at its peak. All in all, Dawson’s first concern is for his readers to use their cellars to taste and experiment.

While chapters three and four are perhaps the book’s most immediately useful, the second chapter is arguably its most important. This is where the chemistry is explored, and it is this knowledge that will equip the serious beer drinker to make informed decisions about which beers to age and when to open them.

In many respects, this chapter is excellent. For the non-chemist, it presents some key concepts and processes in a simplified way that is much easier to understand and retain than the fuller treatment they get in George Fix’s classic Principles of Brewing Science (Brewers Publications, 1999).

We learn that melanoidins in roasted malts are reductones that consume damaging oxygen, slowing down a beer’s ageing process in much the same way that grapeskins do in fine wines. This is why darker beers often mature more gracefully than pale ones. They also contribute caramel and sherry flavours as they themselves become oxidised. We learn how esters are created from the reactions of acids with alcohols, and how the oxidation of those esters reproduces in beer the same flavours and aromas that we associated with drying, ageing fruit. And we come to understand how boozy, solventy fusel alcohols develop complex flavours via oxidation.

The discussion of hops and ageing in this chapter is especially good. It’s very useful to know that selecting for the cellar is not just about avoiding hoppy beers, but about avoiding high levels of alpha acids, specifically. Through the isomerisation in the boil that creates bitterness, these acids become very susceptible to oxidation, which can generate the unpleasant, “cardboard” flavour of the trans-2-nonenal aldehyde. Beta acids, on the other hand, degrade much more slowly and can generate desirable methyl-butyrate esters as they do so – helping an aged beer to retain some of its bitterness and develop winelike flavours. Noble and English hops tend to fit the profile well.

There is also a good section on open-fermented beers and their particular flavours, derived from Brettanomyces yeast strains, Pediococcus, Lactobacillus and Acetobacter, which offers some insights into why these generally low-ABV beers have such great ageing potential.

A helpful companion

The section on oxidation – in so many ways the key to ageing beer – is a decent introduction to the basic chemical processes. However, sometimes over-simplification leads to a lack of clarity. Throughout, it’s never clear whether Dawson is describing oxidation processes (an oxygen electron moving from one non-oxygen molecule to another) or auto-oxidation processes (an oxygen electron moving from an oxygen molecule to a non-oxygen molecule); which is more common; and whether this matters. Indeed, auto-oxidation is not mentioned at all. Oddly, he describes the molecule that loses its oxygen electron as the one that has been oxidised.

These could be simple proofreading errors, but they inevitably raise questions about how precise the details in this chapter are. Most of it appears sound to me (a non-chemist), and it does present the basics in an easy-to-retain fashion, but I would recommend using this book in combination with Fix’s, especially for a fuller understanding of oxidation processes.

The next two chapters take these insights on beer chemistry and explore the implications as to which beer styles will survive and develop with age, before presenting detailed vertical tastings of specific examples of “common, yet exceptional, brews that are considered benchmarks for what their beer style can achieve with time”. These tastings, conducted by the author and “a panel of experienced beer aficionados”, are summarised in handy “ageing profile charts” that enable the reader immediately to see which flavours are likely to define a beer at various points in its ageing career.

Ageing at a glance

Much of this follows naturally from the science in chapter two. English Barley Wines are the classic age-worthy beers because their hops tend to be higher in beta than alpha acids, and they utilise low-attenuation yeasts that are stressed by high-gravity wort into producing an abundance of esters and fusels that develop in complexity with oxidation. It is interesting to learn that these beers were built to last to an even greater degree decades ago than they are today, reminding us that, appropriately enough, ageing beer is not merely another trendy obsession of the geekocracy.

Similarly, Strong Dark Belgian Ales (“Quadrupels” or “Quads”) last well because these sparingly-hopped beers turn instead to spicy phenols for their aromatic top notes, which create a foundation for the laying down of vanilla and tobacco over time. Like English Barley Wines, their high ABVs allow these chemical processes to proceed gradually.

If Barley Wines and Strong Dark Belgian Ales intensify over time, Gueuzes oscillate between sourness, funkiness and complex fruitiness through time. These relatively low-ABV beers can survive for many years mostly because they are highly-acidic, but also because the Brettanomyces yeasts continue to metabolise for an unusually long time inside the bottle, consuming oxygen. This means that the oxidation-related flavours so characteristic of other aged beers, such as sherry, caramel and toffee, do not develop in Gueuze. Instead, they increase in sourness for their first few years, as the Brettanomyces yeast and Pediococcus bacteria consume the younger, sweeter Lambic of the Gueuze blend and produce more acid. At around four-to-six years, those acids react with the alcohol to bring forward funkiness, rhubarb, honey, and other complex esters. Finally, as these beers take on serious age, these esters fade and leave behind a return to sourness, this time with a more vinous quality.

Things become a little more problematic as the book addresses some of the other beer styles, which appear to have been included for completeness despite the fact that they often do not age particularly well beyond a couple of years.

Imperial Stouts, for example, will develop pleasant black-cherry flavours as the dark-roasted malt character blends with fruity esters, but things start going south after two or three years as hop alpha acids oxidise and the acidity of those dark malts accelerates autolysis (or yeast death and degradation).

Dawson acknowledges that American Barley Wines are not designed and brewed for ageing in the way that English ones are, not least because they are quite hop-forward. They are included here because they are more widely available and because they “do something that the English barley wines never pull off, and that is to combine quality, aged malt flavours (sherry) and an extraordinary hop presence”.

I was particularly interested to read about Flanders Red and Brown Ales, having been surprised to find that one of my favourite examples, Duchesse de Bourgogne, ages very badly, losing much of its character after a mere six-to-nine months in the cellar. I assumed this had something to do with the fact that the beer is pasteurised, and therefore especially vulnerable to oxidation because there is no live yeast around to soak up the oxygen in the bottle.

Dawson confirms these assumptions (Rule No. 12), while adding the obvious point that barrel-aged beers have already undergone substantial oxidation even before they are bottled. He explicitly warns against cellaring barrel-aged beers for too long for this reason. He selects Rodenbach Grand Cru for the vertical tasting, apparently because it has a high level of acidity that slows down oxidation and allows those flavours to develop more gradually. However, it seems that it is the high levels of lactic acid, specifically, that work well, and that the presence of acetic acid from the Acetobacter harboured by the “foeder” barrels will lead to less-desirable solvent flavours over time. This might explain why Duchesse de Bourgogne – whose wonderful bite and balance derives from its balsamic-vinegar notes – does not age well.

In a similar vein, Dawson suggests that lower bitterness and the use of high-beta acid Cascade hops are characteristic of those American Barley Wines that will stand up best to ageing.

But of course, in both instances this begs the question why one would choose these styles to cellar in the first place, rather than the Baltic Porters, Rauchbiers, Tripels and Dubbels that Dawson excludes. These “can age well”, he writes, “but some examples are better fresh, so they need to be judged on a case-by-case basis”. This seems to describe the American Barley Wine and Flanders mixed-fermentation styles equally well.

The downside of identifying a number of styles as age-worthy, and then going for “completeness” by tasting only one beer from each of those styles, becomes clear as we move into the chapter detailing the vertical tastings. It pushes out some beers that would age wondrously over 10 or even 20 years in favour of others that struggle to hold their own beyond three or four. A hint of what might have been is given in Dawson’s vertical tasting of Schneider Aventinus, a beer that, as I have just discovered, is a surprisingly outstanding candidate for cellaring that does not fit into the book’s chosen styles at all. If we can include this, why not an example of what happens to an ageing Rauchbier, which would have been fascinating? And, while there may not be much to gain from comparing vertical tastings of several Strong Dark Belgian Ales, there certainly would have been interest in doing so for a range of Gueuzes, rather than just the single example of Drie Fonteinen, fine as it is.

These seem to me to be stronger candidates for inclusion than Brooklyn Brewery’s Black Chocolate Stout, with its shelf life of three or four years – albeit that some interesting flavour evolutions occur in this beer during its first two years in the cellar. If this was a question of space in the book, the publisher might have considered dropping chapter six altogether, which, aside from an informative section of cellar-management apps, offers little more than common-sense advice on keeping track of your beers in a notebook or spreadsheet. After all, the contents of Dawson’s cellar and his priceless experience in tasting aged beers are the real reasons we turn to his book.

Finally, there is a rather fundamental question that is perhaps not addressed in Vintage Beer as fully as it ought to be. Dawson claims that, “batch to batch, variations in a beer are fairly minor (with the exception of wild or Lambic styles), which enables an experienced beer connoisseur to have a fairly good idea of what the brew will do as it ages”.

This seems like a bold claim. Dawson notes that beers older than 15 years were not included “because of the extended effects of bottle-to-bottle variation”. However, there is surely also considerable risk that the recipes, and the quality of ingredients at the same brewery, have varied significantly from one year to the next, obscuring the extent to which vintage-to-vintage comparisons are determined by ageing processes or by these variations. Indeed, in the vertical tasting of Trappistes Rochefort 10 the panel note that head retention follows a bell curve across vintages, “leading one to wonder if a change in brewing or recipe is the culprit”. It’s a question that haunts the entire chapter, and could have done with a more in-depth, considered discussion.

Overall, Dawson has given us a handy, easy-to-use book on a topic that is attracting more and more attention from beer drinkers, and has been in need of serious treatment. The approach he has taken seems to be the right one: outlining the important chemical processes involved in beer ageing, and extrapolating some clear selection criteria based on those fundamentals. The philosophy is to provide the reader with the basic knowledge required to select beers for cellaring, and to decide how long to cellar them for, and that is refreshingly different from the “1000 Beers to Try Before You Die” approach of many beer guidebooks. If anything, I should have appreciated a few more of Dawson’s personal choices in chapter four.

One of those choices might have been Orval. Orval does get a mention. Is it enough of a mention to explain the experience I had with this beer at five years old?

“Given a year in the bottle… [Orval’s] unique Brett strain transforms the beer into a crisp, floral ale with layers of brett-induced intricacy. It continues to develop over the years, but most find it overwhelmingly phenolic around the three-year mark… [at this point it] is extremely dry and loaded with so much funkiness that it will be too unbalanced for most – excluding only the biggest Brett fans.”

To be honest, the answer is yes and no. Like so much in this pioneering book, it offers tantalising glimpses of what might have been.

Pingback: Brew Day!… “Pacific Northwest” | Pursuit of Abbeyness

Pingback: Brew Day!… Revisiting “Pacific Northwest” | Pursuit of Abbeyness

Pingback: Brew Day!… “Memento Mori” Barley Wine | Pursuit of Abbeyness

Great post! I’ve only been home brewing for a few months but already it’s become evident that I’m going to need to age a lot of my bottles – that or give them away. Plus I managed to get some Goose Island Bourbon County late last year. I think I’ll try to forget I own those bottles for a few years and see how they develop.

LikeLike

Thanks! I am most into Belgian styles, so ageing my homebrew isn’t usually a problem. When I have made high-alpha hop styles, I have been surprised at how rapidly the flavours change.

A friend of mine was kind enough to pick up one of those Goose Island stouts that were released before Christmas. I reckon it will do well over 3-4 years. I think longer might be a slight risk, but one never knows!

LikeLike

Pingback: Store in a Quiet Place, or Tweeting in Tynt Meadow | Pursuit of Abbeyness

Pingback: Economy of Means | Pursuit of Abbeyness

Pingback: On Clones, Colour and Cassonade | Pursuit of Abbeyness

Pingback: Brew Day!… “Cuvée Covid” | Pursuit of Abbeyness